Researchers Advocate for Federal Public Health Approach to Address Opioid-Exposed Infants

October 26, 2021 / by Michele Carroll- Research

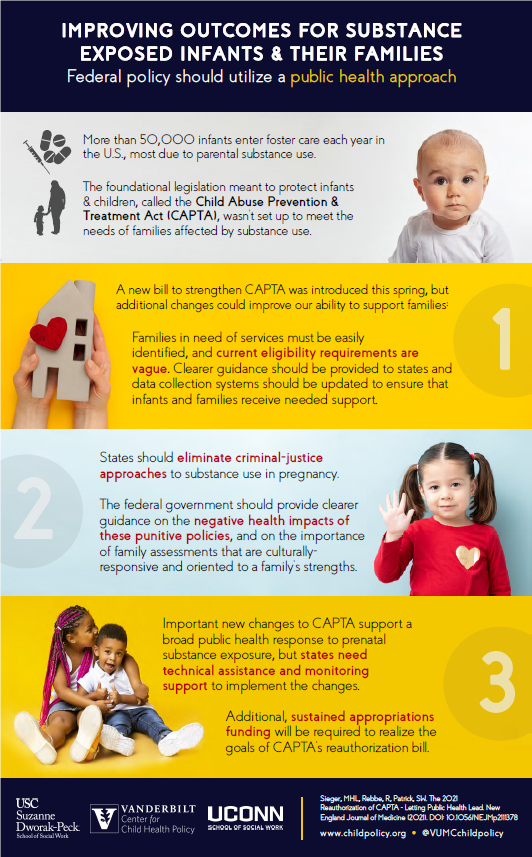

Over the last decade, as opioid abuse has become a national epidemic and the number of infants and young children removed from their families because parental substance use has risen, federal child-protection policies have struggled to keep pace. Currently, the foundational child-protection legislation in the United States, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), is up for reauthorization in the U.S. Senate and includes significant changes aimed at better addressing this crisis.

Assistant Professor Rebecca Rebbe of the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, Assistant Professor Margaret Lloyd Sieger of the University of Connecticut School of Social Work, and Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Health Policy and Director of the Vanderbilt University Center for Child Health Policy Dr. Stephen Patrick have co-authored a Perspective article published in The New England Journal of Medicine on October 23, 2021. “The 2021 Reauthorization of CAPTA — Letting Public Health Lead” advocates for greater clarity and dedicated funding to support successful implementation at the state level.

“CAPTA is the big communicator from the federal government to the states about what they want to see happen in child protection,” Rebbe said. “We think this is an opportunity for CAPTA to take a public health approach to child maltreatment and opioid-exposed infants to help strengthen families rather than automatically separate them.”

Catching up to contemporary issues

The new legislation seeks to catch up to contemporary issues facing children and their families, including significant new provisions designed to address infants born affected by parental substance abuse, most importantly due to the current opioid crisis. In its nearly 50-year history, CAPTA has been updated more than 20 times; however, it has often fallen short of addressing shifts in the social landscape to reflect current concerns and priorities. For example, it was not until the early 2000s that CAPTA covered infants who had been exposed to drugs or alcohol in utero, as the researchers point out in their article.

Meanwhile, the problem has continued to grow. While data varies widely due to reporting inconsistencies, some reports suggest that up to 40% of confirmed cases of child maltreatment involve the use of alcohol or other drugs by a parent or caretaker. It has also become a significant public health cost, with one study estimating that states spend $5.3 billion annually on child welfare costs related to substance abuse.

“This reauthorization offers a chance for states to receive more tailored guidance in implementing their own multi-disciplinary strategy,” Lloyd Sieger said. “But, in order for its passage to make a difference, healthcare providers need to know about the policy, some of its nuance, and areas where additional support will be needed.”

Clinical clarity must replace vague terminology

One of the biggest challenges Rebbe and her colleagues identify is the vagueness in the current draft of the CAPTA reauthorization bill. While well intentioned, the bill still contains unclear terminology that is likely to encourage inconsistent application and underreporting that would create wide disparities in the accuracy of data state to state. Most critical is the emphasis that eligible infants be “affected by” drugs or alcohol, a term which has no defined clinical meaning.

“We know from a public health standpoint that having clearly defined terminology is essential to not only identification and treatment, but also consistent data” Rebbe said. “This is even more true with child maltreatment, where this phenomenon has different definitions.”

Supporting families rather than punishing them

The CAPTA reauthorization aims to support families rather than punishing them, recognizing that a comprehensive, service-oriented approach is appropriate to deal with this issue. One key recommendation is to shift the focus from infant diagnoses alone to the use of parental diagnoses in order to approach the family systemically and increase the probability of keeping parents and children together where appropriate.

“Treating this as a public health issue rather than a punitive or even criminal one humanizes potential treatment and care plans for the entire family,” Rebbe said.

However, there are a number of states that take a punitive or even criminal approach to substance use during pregnancy, which can have the unintended consequence of reducing reporting. Some of the areas hit the hardest by the opioid crisis actually have the lowest reports under the limited National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) definition. For example, West Virginia has the highest rate of opioid-addicted infants in the country, but it is also among the states with lowest rates of child-maltreatment reports that meet the NCANDS definition. This apparent underreporting keeps both parents and their children from receiving the treatment they need and states from receiving the funding needed to support them.

How COVID has impacted child maltreatment

Prior to becoming a researcher, Rebbe was a public child welfare social worker for six years, so she brings a real-world perspective to her research. Rebbe recently received a two-year grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund a study that will empirically examine the impact of COVID-19 on child maltreatment. The study will be conducted by Rebbe through the Children’s Data Network at the Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, in collaboration with Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego.

This research will combine California child protection data with data from a full spectrum of medical encounters, including regular wellness visits as well as hospitalizations and emergency room visits. This will allow for triangulation of data to gain better insight into whether maltreatment encounters have changed as a result of COVID-19 and the increased stress it has placed on family systems. It will also examine whether reporting behaviors by medical professionals have changed as they are aware that children’s exposure outside the home is limited and the burden falls on them to report.

The examination of federal policy regarding opioid-exposed infants and the reporting behaviors of medical professionals fits squarely into Rebbe’s research agenda focused on how communities respond to child maltreatment. “Child maltreatment is a complex public health issue with detrimental outcomes,” Rebbe said. “However, how to respond to maltreatment is an immense challenge for communities, systems and professionals because there are no easy solutions. My work examines the different approaches with the goal of improving outcomes for children and families.”

To reference the work of our faculty online, we ask that you directly quote their work where possible and attribute it to "FACULTY NAME, a professor in the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work” (LINK: https://dworakpeck.usc.edu)