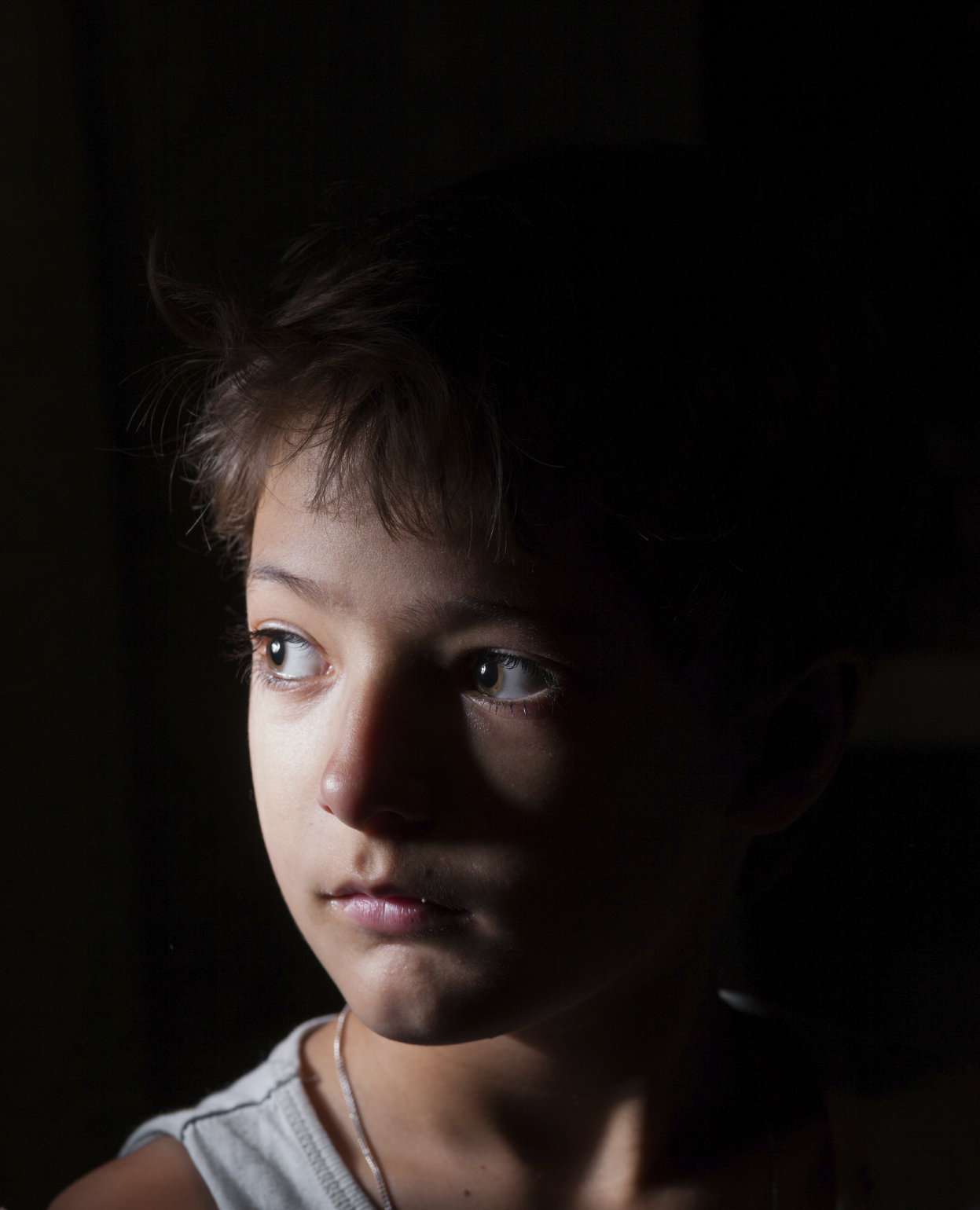

The Overlooked Trauma of Children with Parents Behind Bars

August 25, 2017A significant portion of incarcerated individuals are parents. More than 2.7 million children in the U.S. have an incarcerated parent, and more than 10 million have experienced parental incarceration at some point in their lives. Those numbers are even higher when including children with parents under active supervision, parole or probation.

For these children, the experience of having a parent arrested and incarcerated is often very traumatic. And while incarcerated people may have access to pre-release programs that provide assistance in planning for the basics of successful re-entry into society—things like transportation, temporary housing, obtaining identification, job training and education—they frequently do not receive counseling on successful re-entry into family life.

This trauma experienced by children is not talked about enough, and two USC experts want to change that.

Increased Risk for Toxic Stress

“Children with incarcerated parents can feel confused, guilty and even responsible for their parent’s incarceration,” said child grief expert David Schonfeld, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician, director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement and professor of practice at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. “Our penal system is focused on both rehabilitating and punishing incarcerated individuals. The problem is if we don’t help them maintain connections with family, it makes it less likely they will return to a parenting role, and that punishes the child, too. This compounds the child’s feelings of guilt and responsibility.”

Peter Breen, MSW ’67, also believes that children with incarcerated parents are not receiving the emotional care and attention they need. A retired welfare director in Marin County, California, Breen serves on the board of Centerforce, a nonprofit organization that provides support services to incarcerated individuals and their families at various state and county correctional institutions.

“These kids are experiencing enduring, insidious trauma while their parents are in prison,” he said. “They are often subjected to ridicule and bullying as a result of having an incarcerated parent. Kids don’t want to talk about it, people don’t know about it, and as a result, education folks aren’t always sensitive to the trauma. Most teachers haven’t had any training or information about how to understand these particular children, and more needs to be done for them.”

In a 2015 report based on data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, nonprofit organization Child Trends found that there is an alarming collection of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) affecting children with incarcerated parents. These experiences are associated with increased risk for trauma, or toxic stress, particularly when they are cumulative. When a child’s parent is incarcerated, traumatic stress may occur through multiple pathways. The loss of an attachment figure, and ongoing contact with law enforcement, judicial, corrections and child welfare systems can all contribute to further traumatization.

More Coping Tools and Support are Needed

Direct interventions are needed to help reduce the trauma and stigma these children experience. New programs and funding can facilitate improved communications between children and their incarcerated parents, and can help families and neighborhoods manage the challenge of coping with separation. There is a dearth of such interventions in the correctional system countrywide, but Schonfeld and Breen are two examples of people who are bridging the gap.

“Parenting can happen during incarceration,” said Schonfeld. “School programs and sensitivity in structuring assignments and curriculum can help facilitate continuing bonds between incarcerated parents and their children. Sometimes, it’s possible for the parent-child relationship to even deepen as a result of these efforts.”

Advocating for Children of the Incarcerated

For members of the social work community who want to help this vulnerable and often overlooked population of children, there are several ways to do so.

Breen recommends individuals contact a local sheriff or community partner manager and offer assistance to programs they might already have for children and families. If there aren’t any, volunteer to start a new program or offer a new service. Encourage colleagues and fellow social workers to do the same. Help raise awareness.

Policy advocates and agency administrators can encourage policies within the judicial system that support the need to inquire about family relationships and impact in every new case. They can also work to develop tailored, comprehensive training for teachers, social workers, foster parents and Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) volunteers who work with children and families affected by incarceration.

Schonfeld and the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement have partnered with New York Life Foundation to form The Coalition to Support Grieving Students, which offers practitioner-oriented information, insights and practical advice designed to help educators and school personnel work with grieving children. Free videos and learning modules are available for download available on their website.

Sources:

Mauer, M., Nellis, A., Schirmir, S.; Incarcerated Parents and Their Children - Trends 1991 - 2007, The Sentencing Project, Feb. 2009

Murphey, D., Cooper, P.M.; Parents Behind Bars: What Happens to Their Children? Child Trends, Oct. 2015

The Pew Charitable Trusts: Pew Center on the States. Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility. Sep. 2010