School Challenges Status Quo on Poverty at All School Day Event

February 27, 2017 / by Maya Meinert- Alumni

About 10 percent of the world’s population, or 767 million people, lived on less than $1.90 a day in 2013. A vast majority of the poor live in rural areas, are poorly educated, mostly employed in the agricultural sector, and more than half are under 18 years of age. And while incomes increased from 2014 to 2015, the 2015 poverty rate was 1.0 percentage point higher than in 2007, the year before the most recent recession.

What does all this mean for the vulnerable populations social workers and nurses serve?

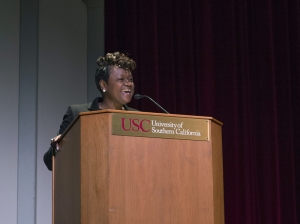

The answer to that question was the focus of this year’s All School Day event, hosted by the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work at Bovard Auditorium on Feb. 15. The theme of “Human Dignity: How Poverty Affects Human Rights” featured speakers from various areas of study, including law, filmmaking, social work and nursing, to encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration in addressing the effects of poverty.

Dean Marilyn Flynn pointed out how society often discusses the effects of poverty, such as poor health, unemployment and homelessness, but rarely does it dig deep enough to address the root cause.

“Poverty underlies every manifestation of serious challenges to families, children, aging persons, refugees and all the populations we see every day [as social workers and nurses],” she said. “I hope this is the beginning of a reframing in our school of the word poverty and what it means for human rights, how it connects to social justice and what it means for human dignity.”

All School Day, an annual educational forum co-led by students and faculty, began in 1992 after racial tensions sparked civil unrest in Los Angeles. Each year since, the school has brought people together in an atmosphere of cooperation, respect and inclusion to raise awareness about diversity and to discuss how society can better communicate across differences in race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, age, social class and disability.

Cherrie Short, associate dean of global and community initiatives, organized the event with the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights in mind.

“[The Declaration] says we have the right to basic living needs, such as a home, access to clean water and food, and the right to security during times of conflict,” she said. “As social workers, we understand that not all people have access to these basic needs. We also know that poverty contributes to serious global issues, such as war, famine and unrest. Today we come together to discuss how these issues can focus the thinking in our work as part of our ethics and values as social workers.”

Personal experience

Alicia Cass, MSW ‘07, gave an impassioned speech about the vital role social workers play in the lives of their clients. Cass knows what it’s like to be part of a vulnerable population: After her mother died when she was 4 years old, she experienced sexual abuse, began selling drugs at 12, joined a gang at 13, was in and out of foster care until 15 when she became pregnant with her first child, became a single mother when her daughter’s father was murdered, became homeless, dropped out of school, had two more babies by 19, was in a domestic violence relationship at 23, was in public housing and on welfare, had six kids by 26, and now at 46 years old has eight children.

“I didn’t realize I was in a vicious cycle stemming from poverty. When you’re in the midst of it, you don’t have a clue,” she said. “As I was writing my book, I started to see that my family couldn’t protect or help me because they couldn’t protect or help themselves. They don’t know that they’re in it because this has become their norm. This is generational.”

Cass, who is the founder of The Metamorphosis Experience, which assists and supports women and youth in underserved communities, told the audience of students that their roles as social workers and health care professionals will have a profound effect on people like her.

“You have the power of words. You have the power to encourage. You will let them know that this will not keep them down, they will not stay stuck where they are,” said Cass, who is now working toward receiving a doctorate in education at USC. “You have the ability…to change lives, and not just their lives but their children’s and children’s children’s lives. You will change communities, and you will change generations.”

Different avenues

Lucy Williams, who directs public interest and pro bono legal initiatives at Northeastern University, spoke to the audience filled with social work and nursing students on the constitutionality of human rights and how poverty is antithetical to the ideals of democracy.

“[Government] must take positive steps to allocate resources in a way that enables all people to lead a sustainable and dignified life,” she said. “Poverty and democracy are incompatible. Citizens living in poverty cannot participate meaningfully and authentically in self-government. They cannot self-determine their lives as individuals, as families or as community members.”

However, Williams admitted that just because social and economic rights are written into a constitution does not mean that poverty would be automatically eliminated.

“Law on the books and law on the ground are two very different things,” she said. “History teaches that courts and legislatures typically do not take needed steps to give meaning to legal rights unless they are pressured to do so by grass-roots organizations. Rights are worth no more than the paper they are written on if grass-roots communities and advocates do not use this space…to empower people to claim what is their due.”

Documentary filmmaker Amy Ziering, best known for her films “The Invisible War” and “The Hunting Ground” that put faces on the controversial subjects of sexual assault in the military and on college campuses, respectively, explained how using film can amplify the advocacy work that social workers do on the ground.

“Storytelling and what you say is something to be taken very seriously. It’s both important and difficult,” she said. “Words matter. You have to take care, and there’s a profound responsibility involved.”

Ziering’s films have served as the impetus for numerous Congressional reforms.

“We write our own stories through each other. It’s a reciprocal and dependent relationship,” she said. “Life is a collaboration, and we really are each other’s stories.”

Looking at the impact

During the panel, which included Ziering, along with Niels Frenzen, director of the USC Gould School of Law Immigration Clinic, and Ellen Olshansky, chair of the Department of Nursing at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, the speakers discussed how their respective areas of expertise view poverty and its effects on people.

“One’s socioeconomic status affects one’s abilities to come to the United States,” said Frenzen, who discussed the history of immigration to the United States. “It wasn’t until the late 1800s that the federal government started to impose restrictions on who could come here, and one of the first restrictions was on paupers, or poor people. That’s still in our law. Poor people are not welcome to the United States.”

Frenzen also pointed out the differences between people who can afford to come to the United States via airplanes versus those who can’t even qualify for visas due to their poverty.

“People who can afford air travel don’t have to subject themselves to this process,” he said. “It’s the ones who can’t afford it who walk, ride on the backs of trains and pay a smuggler to take [dangerous] migrant boats.”

Representing the health care angle, Olshansky emphasized the natural partnership between social work and nursing, as the Master of Science in Nursing program at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work focuses on community health and the effects the social environment has on health.

She pointed to several examples of inequities stemming from socioeconomic status, including how access to health care is not enough if the ensuing treatment is not fair, how domestic violence saw an uptick during the most recent recession, and how defunding family planning services such as Planned Parenthood limits access to reproductive health to only those who can afford it.

“In order to address the health care needs of our patients, we must address their social context and social justice,” Olshansky said. “People who have less, people who live in poverty, people who are not afforded the dignity that all human beings have suffer in ways that other people do not.”

To reference the work of our faculty online, we ask that you directly quote their work where possible and attribute it to "FACULTY NAME, a professor in the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work” (LINK: https://dworakpeck.usc.edu)