Healing a Community with Consistency, Compassion, Empathy

April 21, 2020 / by Jacqueline Mazarella- Practice

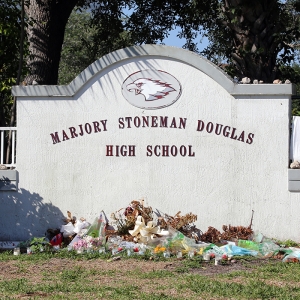

On February 14, 2018, a 19-year-old gunman walked into Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, and opened fire, killing 17 students and faculty members, and injuring 18 others.

Within walking distance from the school, Lisa Wobbe-Veit, clinical associate professor and south regional director for the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, arrived at her son’s elementary school to treat him to a special early pick up for Valentine’s Day. She found the school closed, on lockdown.

“Parkland is small,” Wobbe-Veit said. “All of our schools are walking distance to the high school for the most part, so all the schools were on lockdown that day… that is kind of where it began, supporting families outside of that school.”

Wobbe-Veit quickly reached out to her son’s school principal, to the mayor and to her school board member to identify resources she had at hand. She was worried about what they were going to say to her child the next day at school and wanted to ensure they had appropriate resources available.

Knowing the benefits of having a social worker to support families after violence, Wobbe-Veit wanted to provide information and experts in the field so that her community had the best support as it went through the next steps.

“There’s so much that needs to happen to support families post-individual acts of violence or mass violence, and it’s ongoing,” Wobbe-Veit said. “Oftentimes there’s a lack of information or maybe awareness of the impact these types of tragedies have on families financially, emotionally and how long they last.”

Wobbe-Veit asserts that she can only speak for how she felt, as a mother who knew her children were safe. However, she is comfortable saying that everybody in the community has been impacted, and she believes those in support positions need to holistically think about supporting children, families, teachers and administrators.

Now, Wobbe-Veit works as a consultant for Broward County Public Schools. As she puts it, she supports the district around the tragedy.

The initial aftermath

Lisa Olson, a teacher who works with children with learning disabilities, was at her elementary school only one mile from Marjory Stoneman Douglas the day of the shooting. Her son, William, a ninth grader at Stoneman Douglas, was in the first classroom where the shooter opened fire. William was shot in his arms, the boy sitting next to him was murdered and two boys across from him were also wounded. William still has shrapnel in both arms that are not able to be removed.

“It was the worst day of our lives, but it was also the best day because he got to live,” Olson said. “The chaos was so random that my husband and I feel we won the lottery because we were so fortunate William came home to us.”

In the very beginning, there was no contact for injured families to help them with anything, Olson said. Less than 15 days after the shooting, all the children were invited back to school to see their teachers and retrieve their backpacks.

“The school opened way too soon,” Olson said. “They were not prepared for the children to come back. The teachers were traumatized, the students were traumatized, it was terrible.”

William’s name was left off the injured list, so his teachers had no idea what had happened to him. Olson felt the school was not helping her family or any of the children. After confronting the guidance department that day, she agreed to have a social worker connect with her.

“Michele Myette became the most amazing person for our family to go through this awful experience with,” Olson said. “She had such compassion, I could trust her. She had such empathy and she was doing whatever she could to help us to navigate through.”

Myette talked with Olson day and night. “She was the only person I had, and I don’t think―I know―we couldn’t have managed without her,” she said.

Olson felt Myette had her finger on the pulse of what her family needed; that she spoke out for and supported them. But, there was a disconnect with the district in understanding how important the relationship between her family and the social worker had become. Myette worked for another school, and Olson felt that the district wanted to get her back to her original position. At the same time, a new onsite liaison was introduced for all the injured families.

For Olson, introducing the new liaison with whom they had no relationship, felt like another loss for them. She and her family had built such a close relationship with Myette, and Myette had provided them so much vital assistance. Now, Olson and the other parents of injured children were told to direct any inquiries to the new liaison. Olson felt betrayed.

“I remember calling [the new liaison] and saying, ‘please can you help me get my son's textbooks,’” Olson said. “He can't go into a cafeteria of a thousand children. He can’t. He physically and emotionally can't handle that. I felt like I was asking for help from a stranger rather than someone that had already been a part of what our family was going through.”

Olson recalls that Wobbe-Veit had been in the background since the beginning, and the families felt that she was part of their community and they were comfortable going to her. Wobbe-Veit had continued to volunteer her time in the school district for the first ten months after the shooting, but now she was going to play a contracted role.

Wobbe-Veit told Olson and the other parents of injured children that she would help them. “And she did,” Olson said. “Lisa has been steadfast, consistent, empathetic. She voices our voice and we have a relationship with her.”

Wobbe-Veit was able to step in and provide the connection and trust that Olson needed, and to bond all of the families of injured children together as a group.

“Lisa is there for us individually, but also in unity for the injured families,” Olson said. “She has helped us build this rapport amongst us and we trust her.”

Pillars of strength

Wobbe-Veit expanded the injured parents group to include Stacey Lippel, an English and creative writing teacher at Marjory Stoneman Douglas who was injured that day. Lippel was teaching her creative writing class of 9th to 12th graders when they were ambushed by the shooter. She had not been offered any type of special support as an injured teacher, but Wobbe-Veit recognized that she needed to be a part of this group.

Lippel and her class had responded to what they thought was a routine fire alarm, which they did not know had gone off as a result of the smoke from the shooter’s rampage. They were on the third floor of the building and could not hear the shots on the first floor.

The 38 students in her class gathered their things and headed down the stairwell as Lippel locked her classroom door.

“I didn’t hear any gunshots initially. I just heard them yelling, running and screaming and it was like a log jam,” said Lippel. “Everyone was going down the stairwell and now they were trying to get up the stairwell.”

Lippel immediately turned back to her classroom, unlocked her door and held it open for students to get inside. That is when Lippel saw the shooter.

“He’s just firing all over the place and I’m still trying to pull in kids,” Lippel said. “And somehow when I was out in the hallway, I was shot in the arm.” Lippel held her door open until the very last minute, then pulled it closed and jumped to where the students were hiding.

“And then we just heard him shooting down the hallway. It seemed like forever,” Lippel said.

When Lippel and her students were finally led out of the classroom, what they saw looked like a war zone. SWAT teams tried to block the view of murdered victims, but they were still visible. Hallways were filled with phones, papers, pencils and backpacks.

“That’s a horrible visual that’s ingrained in everyone’s brain,” Lippel said. “So think about that as a layer of trauma. Maybe you don’t necessarily see anything, as things were going down, but then you’re walking out of your classroom and passing all of this.”

According to Lippel, the administration never reached out to offer her support, and all the teachers were expected to simply “soldier on” as beacons of support for the students.

“We were put right back into the saddle, the scene of the crime,” Lippel said. “We had traumatized students in front of us and we were traumatized. But we were expected to be pillars of strength.”

Lippel and the other teachers wanted to be there for their students, but they were unprepared.

There were added layers of stress for Lippel―she was injured, and her own children were students at the school. Initially, she and her family were also not included in the support group for injured families.

“I wasn't part of this group until Lisa came on board,” Lippel said. “The other parents didn't know me, but they knew there was a teacher who was injured and they wanted to know, well, what is that teacher getting? Is that teacher getting support? They were worried about me.”

Lippel believes every family that had a member who was injured should have been assigned to a person who could guide them through how to get help. Her children, who were in class at another building on campus, initially thought she was dead. Her husband thought his entire family was in danger. They were all suffering with levels of trauma.

The superintendent was looking at the entire school as a whole, instead of identifying that different groups had different needs, Lippel said.

Wobbe-Veit, Olson and Lippel all agree that in these types of situations, families do not actually know what they need. The job of a social worker is to assess what those needs are and help guide and inform in a trauma-sensitive way.

Lippel said one of the most important things the parents sought for their kids was someone who could speak to the teachers and the guidance counselors, and assist the students with their academics because they were all falling through the cracks. Wobbe-Veit became that person.

“For me, what I would have needed, back in the beginning, was a trauma-trained specialist to be with me every single period,” Lippel said. “To assist me in handling my students because I was absorbing all of their trauma and still trying to process my own.” At the time, she was unaware that these specialists existed or that she could ask for this type of assistance.

Social workers have the playbook

It feels good to have someone like Wobbe-Veit standing beside them, Olson said. Wobbe-Veit is a great communicator, with a lot of drive for the group, anticipating their needs, curating important information and disseminating it to them.

“She advocates for us, and that's really what we need,” Olson said. “We still have struggles, but she is always there. She'll immediately help you and I do really, really appreciate it because you need that support when you go through something horrific like this.”

It can be hard for social workers because there is often a disconnect from the leadership.

“I feel like people have to think ahead when you’re involved in something like this. You need the consistency and that is so important,” Olson said. “It’s very difficult to explain your story all over again and then build relationships and bond.”

Wobbe-Veit’s role in dealing with a lot of small details that add up to bigger factors is extremely impactful and helps to reduce stress for members of the group, from ensuring they have parking and seats for school-wide meetings, to arranging for the superintendent to speak to their group directly and hear them.

“Lisa is like the little rock of our group,” Olson said. “She is the first one in the parking lot for an event and she is the last one to leave. She will talk to you until you’re ready to go home.”

This community also has a trial coming up, and Lippel knows that Wobbe-Veit will be helping them through it.

Many people in the community said there was no playbook for this type of tragedy. Olson heard that dozens of times, but her experience with Myette and then Wobbe-Veit showed her that they had the playbook. In collaboration with families, these social workers were able to assess potential needs.

“If you’re the 6th largest school district in the nation, you should have some type of plan for these types of tragedies because, unfortunately, they’ve happened before,” Olson said.

While initially unable to implement everything, positive changes have occurred through the liaison role between the families and the district. “We’re in a much better place than where we were—just through developing those relationships over time,” said Wobbe-Veit.

Looking forward

Wobbe-Veit wants to take lessons and best practices learned and extend them to a larger system for supporting families around violence. She saw first-hand how overwhelming it is for families to be bombarded with information initially, when they are perhaps not at a point where they can take it in or even remember all of it.

Having one point of contact for questions, concerns, communication of important information and to navigate all the resources is key, as well as identifying a support network.

“Having an advocate or liaison that helps outline and remind and give choice really does help streamline the needs and how to connect to resources,” Wobbe-Veit explained.

For Marie Laman, whose son was also injured in the shooting, recovery after a tragedy can be described as a long, long road. “As a parent, accepting that your child is different, with a completely different set of challenges than before, is difficult to navigate,” she said. “Having a strong support system is critical. A liaison to coordinate with the school and to problem-solve challenges instead of trying to do it myself has been really helpful. Ongoing support and regularly meeting with other injured families to process challenges as a group has had a positive impact.”

Olson also stressed that she wants people to think of the students in the classrooms who do not have access to social workers for help. It upsets her that they and their families are navigating this on their own.

For the community as a whole, February 14, 2020 began A Day of Service and Love to commemorate two years since the tragedy. The event is district-wide, with all schools in Broward County participating. Each school picks their own project to recognize and remember each individual lost, celebrate how they lived, and give back to the community in their honor.

Wobbe-Veit said as a group as they move forward receiving their individual support and supporting one another, there is a desire to help others in their position and to hopefully alleviate some of the challenges they experienced through their knowledge and what they’ve gone through.

Due to her personal experience, Lippel believes that sharing her story is important, and she wants to put herself in the role of support person for others, especially teachers, who are dealing with similar tragedies.

"Unfortunately, we've had a few school shootings after ours,” Lippel said. “I felt equipped enough to reach out to the English department of Santa Fe High School when that happened to say, 'Hey, we just went through this, you can email me and I can tell you some things that might help you, etc.’”

Myette introduced Olson’s family to therapy dogs when William was having a difficult time staying in school. At first, she thought it was a crazy idea, but Myette pressed and it worked. William, with the help of a dog trained to provide affection, comfort and support, started staying in school, and although he still had difficulty concentrating, he was able to get through each day.

Now, Olson and her son have trained their dog to work as a therapy dog as a way to pay it back. “Now we get to help people like they helped William,” Olson said.

“The families have very been open, honest and vulnerable with me,” Wobbe-Veit said. “I listen to their collective voices and they trust I can translate the information and present it in ways others can understand. I am honored they allow me to advocate on their behalf both individually and as a group. It is their input that has provided the framework for how I will continue to support families who experience trauma."

To reference the work of our faculty online, we ask that you directly quote their work where possible and attribute it to "FACULTY NAME, a professor in the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work” (LINK: https://dworakpeck.usc.edu)